Magna Carter Covered Forest Rights, Too

by Llyod C. Irland

(This article is the first in a series, and was originally published in the September issue of Maine Woodlands).

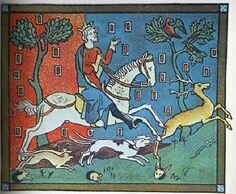

King John

Newspapers and magazines have been reminding us it’s the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta, the “Great Charter” signed under duress by King John in 1215. It turns out that, in addition to protecting the traditional rights of the barons, it also created medieval forest rights that are still with us today.

Almost everyone knows that in 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, defeated Harold Godwinsson, King of England, at Hastings, and took the crown for himself as William the Conqueror. He turfed out the feudal lords owing homage to the crown, replacing them with his own retainers and relatives. England became involuntarily Normanized. What you may not learn in school is that these kings enjoyed the hunt. Medieval monarchs circulated around their domains, requiring hospitality from their barons. At every stop a hunt was virtually mandatory. Hunting was not only recreation, it was business, part of the proper upbringing of a knight or young nobleman. Hunting supplied familiarity with movement on horseback in rugged and unfamiliar terrain, training in teamwork, and exercise in marksmanship – all important martial skills. And the venison was popular at table. Some centuries passed, though, before literacy was considered essential to an aristocrat’s upbringing.

In their legal tradition kings did not own the wildlife, but they controlled hunting rights. King William marked out hunting reserves he personally controlled. These, he called “forests.” The original foresters, then, were the royal game wardens and managers. Historians estimate England at the Conquest was 15% tree-covered (FIA had not yet been invented). Many of the royal forests contained farmland, pastures, marshes, and even villages. Some of William’s Royal Forests exist today, at least in outline and popular geography, though not in legal form. The New Forest is a popular tourist destination.

Within the forests, it was not only unlawful to take venison – the big game, though a modern hunter wouldn’t consider the animals “big” – but also to harm the “vert,” the habitat. So, within the forest’s limits, neither baron nor commoner could clear shrubby or wooded land for crops. The kings also owned manors and woods in their own name, so-called “demesne” lands. But “Royal Forests” were areas where the king controlled the hunt on lands of feudal tenants. The kings at times went to extremes, evicting local farmers and burning villages. The opening of Mel Brooks’ Robin Hood film recalls this.

The King’s control over hunting went down poorly with the lords and barons, who, being Normans, also liked to hunt. Worse, the villeins (farmers) could not kill game animals that fed on their crops. Deer must move freely – no fencing for livestock or to protect crops. Dogs in and near the forest had to have claws removed. “Fence months” were periods when forests were closed to grazing to avoid disturbing does giving birth. Since grazing was a key use, this was a major blow. This was equal opportunity confiscation and oppression, though the poor rarely dined on venison. The Royal Forests disrupted the local economy. Robin Hood got in trouble with the law for two things: robbing the rich to help the poor, and killing the King’s deer.

The Normans and their Angevin successors were serious: Initially, poaching the King’s deer was punishable by death. By 1215, 140 years after Hastings, Royal hunting forests had been extended. They were controlled by Royal “Forrest Lawes,” administered by Forest courts. With this, and various taxes, the barons were fed up. They caught King John at a weak moment, and forced him to sign Magna Carta.

What you don’t learn in school is that among ringing declarations of rights of “free men” – the barons, not the common folk – there were several clauses dealing with forest rights. The subject was so detailed it was soon necessary for the King to issue a separate Forest Charter (1217). It repealed the death penalty for poaching deer, replacing it with a fine, or a year in jail if unable to pay. It created new “verderers courts” to administer the forest laws. Some of Richard’s and Henry’s expansions were “disafforested,” and rights returned to local feudatories and villages. Later, entire books were devoted to details of Forrest Lawes, referring specifically to the Royal hunting forests, not woods and coppices generally.

Does any of this look familiar? The heritage of the Middle Ages influenced English legal thinking for centuries. Massive tomes on Property Law, which law students suffer through, often begin with medieval property rights, including forest law. Under Maine law today, as in Richard’s time, the government does not own the wildlife. Instead, the ‘ferae naturae” are the trust property of the entire society and its people. Government administers them as a trust. Landowners and others often differ on how to manage wildlife, and hunting (Sunday hunting, anyone?) No legislative season passes without the introduction of numerous bitterly contested bills concerning what is to be hunted, when, and how. Some things never change.